Recently 23andMe received FDA authorisation for the first ever direct-to-consumer genetic test for an inherited risk for cancer. Specifically, it tests for variants in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes known to significantly increase the chances of developing breast and ovarian cancer.1

Recently 23andMe received FDA authorisation for the first ever direct-to-consumer genetic test for an inherited risk for cancer. Specifically, it tests for variants in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes known to significantly increase the chances of developing breast and ovarian cancer.1

Anne Wojcicki, the CEO of 23andMe, says that she disagrees with people who believe that patients can’t handle information about genetic disease risk from at-home direct-to-consumer tests like the type her company sells. She likens the public outcry to the position that doctors took 40 years ago with at-home pregnancy tests.1 Reasonable people can debate whether a binary outcome (‘yes’ or ‘no’ to a pregnancy test) versus a test result that could involve the understanding of terms like ‘variants’ and ‘genotypes’ and ‘relative’ vs ‘absolute’ risk is a fair comparison for Ms Wojcicki to make. And we can certainly debate whether the ‘rigorous’ studies and research that Ms Wojcicki alludes to in an Op-Ed she penned for Stat News are comprehensive enough to definitively answer this question (a cursory glance at one study showed the design to be based on semi-structured phone interviews that emphasised patient recall for many key study questions and in which all authors were 23andMe employees and six of the seven held stock in the company).2

The point of this month’s column is not to debate the merits of at-home genetic testing. There are pros and cons to this, as there are for just about anything. But we must not conflate apples and oranges by using comparisons to today’s at-home genetic testing with the home pregnancy tests of yesteryear.

We have learned a lot in 40 years. Especially about health literacy and health information-seeking behaviour. The National Cancer Institute (NCCI) in the US has a wonderful database, the Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS), which can call up important information as it relates to the public’s perceptions, attitudes and basic understanding of information, which sheds light on this topic.

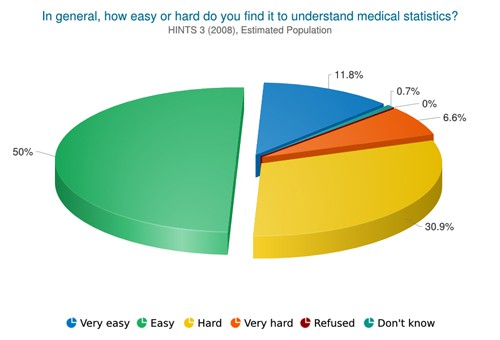

In 2014, one of the HINTS surveys asked respondents whether screening tests (mammograms, colonoscopies, etc) could definitely tell if a person has cancer, and 52% thought this was true. Interesting, isn’t it? More than half of those surveyed believe that certain tests can definitely tell you whether you have cancer. There’s no discussion here of false positives and false negatives. In another question, the respondents were asked if their most recent search for information about cancer resulted in information that they deemed ‘hard to understand’. Approximately 30% of respondents found that the information they were looking for was hard to understand – and almost 37% ‘somewhat disagreed’ that the information was hard to understand. And Figure 1, which is equally disturbing, shows that almost 40% of the estimated population find it hard to understand medical statistics.

I took a look at a few of 23andMe’s sample reports on late-onset Alzheimer’s and Cystic Fibrosis. They seem to be nicely laid out and designed. There are caveats and disclaimers everywhere that serve to remind the recipients that this report is not a diagnostic tool and that they still have a risk of developing the disease in question. And there are ‘genetic health risk tutorial’ links. And FAQ links. Don’t get me wrong: 23andMe is trying. But health literacy is not easily overcome via the use of bold font treatments, eye-catching colours and intuitive icons.

Make no mistake about it: this is an issue of health literacy and health motivation. Can people understand what an at-home genetic test reveals? And do these results motivate a particular behaviour? This is not an issue about test accuracy. We assume these tests are accurate and that someone with some regulatory and scientific expertise has validated this (we have learned from the dark days of Theranos). This is also an issue of health inequalities. At hundreds of dollars per test, are we making this technology available only to those who can afford it and, by extension, to those who can most easily understand the results? Given the strong association between household income, educational attainment and health status, maybe the folks who order these at-home tests are more educated and earn more money.

There is very little debate that the next few years and decades will bring immense change in the amount of information that patients/consumers will be able to access at home through this type of service. Our focus needs to be on making sure that the information being delivered is easily understood, affordable and that we learn from the data that we have at hand from organisations like the National Cancer Institute.

By framing this issue and the resulting criticism as a referendum on ‘genetic testing’ vs ‘at-home pregnancy tests’ attempts to over-simplify the problem as we strive to deliver increasingly complex medical information to patients. Wouldn’t you agree, Ms Wojcicki?

1https://www.statnews.com/2018/04/09/consumers-23andme-genetic-risk reports/

2 https://peerj.com/articles/8/#author-1