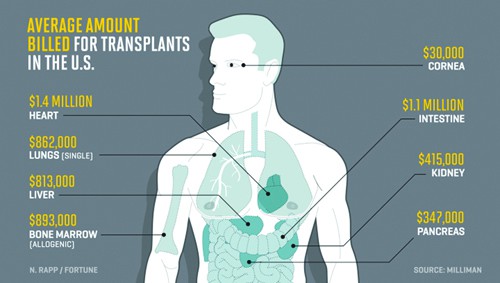

When it comes to organ transplants, with US costs that range from $415,000 for a mere kidney all the way up to $1,400,000 for a heart, price certainly does matter. But it also doesn’t.

Let’s conduct a social healthcare experiment: ask a thousand people if they would be willing to undergo a kidney transplant at 1960s prices – somewhere in the order of a 90% reduction versus today’s prices depending on the country you live in – using today’s medicines and technologies. And tell them that this is not a trick question. The answer would be a resounding ‘yes’. And now ask them if they would be willing to undergo a kidney transplant at 1960s prices but using 1960s technology. This means 1960s surgeons and nurses. This means 1960s immunosuppressive drugs and instruments. And perhaps most importantly, this means 1960s surgical technique and know-how. And, by the way, tell the people that the mortality rates or complication rates are exactly the same between the two choices being offered. Go ahead. Ask. The number of people answering ‘yes’ is pretty low – isn’t it?

We learn many things from this simple question. We learn that if we were to invent an economic principle such as the ‘price elasticity of innovation’, it would demonstrate incredible elasticity. The rate of change of quantity demanded as a function of the state of innovation would be dramatically different for older medicines and surgical interventions as compared to newer ones (most of the time). We also glean from this question that technology matters to individuals at the micro level. At the macro level, policymakers and payers are motivated by different drivers and are forced to consider arcane concepts like the ‘greater good’ and ‘budget impact’. But Individual patients are not. Individual patients want the ‘best’ and the ‘latest and greatest’ for themselves and their loved ones. Have you ever seen an individual patient’s reaction to the choice between a brand name medication and a generic? It’s priceless. Even when told that the generic medication is cheaper and works exactly the same way as the more expensive medication. In some regard, one could say that at the micro level, individual patients are willing to pay for innovation.

And another (hidden) lesson from this social experiment of ours lies in the fact that healthcare is not a public good in the traditional sense. It is a private good. Even when its provision is delivered through the public system or it is financed by the public purse. It is only a public good when its consumption is non-rival and non-excludable. By non-rival, we mean that the consumption by one individual does not reduce someone else’s consumption. And by non-excludable, we mean that a consumer cannot be excluded from consuming the goods either by having to pay for them, or by through some other mechanism.

When a patient ‘consumes’ a kidney, that patient reduces the consumption of a kidney and other ancillary healthcare services for another individual. And when patients cannot pay for their kidney transplants, or the waiting list for end-stage renal disease patients is so long that they die waiting for a transplant, they have most certainly been excluded from ‘consumption’ due to cost or some other means. But individuals don’t think like that. They don’t think about the effect their consumption has on others or what their inability to pay means in terms of the grand scheme of things.

Why does this matter? Because we forget, or ignore the fact, that healthcare is vastly different at the individual level than it is at the population level. This ‘micro’ vs ‘macro’ difference doesn’t just manifest itself in the form of kidney transplants. It’s everywhere. Healthcare matters to actual people. When they need it and not at any other time. And innovation matters to people. And they are willing to pay for it.

And so, in this brave new world of CAR-T and CRISPR and I/O therapies – to name a few – we continue to rely on governments to ensure that these therapies are safe and efficacious. We continue to look to regulators to ensure that access to these medications is available. But we also need to demand from governments and regulators that they not forget that healthcare at its core is about individual patients making decisions about care based on more than just price.