How would you like it if someone showed up at your job, spent 7-12 minutes with you and then posted an opinion of your competency on a widely-viewed website. And what if that person had an axe to grind or didn’t really have the competency themselves to understand whether you were good at your job or not? Or what if that person wasn’t really rating you but was rating a colleague (like a receptionist or a nurse)? Or what if you were just having an off day?

This is happening every day on sites like Yelp, Vitals and RateMDs. There’s absolutely nothing wrong with expressing an opinion about the demeanour of the receptionist, the wait time, the décor of the office or the lack of parking. But when these online sites start accepting random reviews and comments about a clinician’s professional competency (ie misdiagnosis of a condition or a recommendation for a particular treatment approach that was later disputed by a second opinion) or allow allegations about supposed overbilling and innuendo of fraud, we’ve gone way too far.

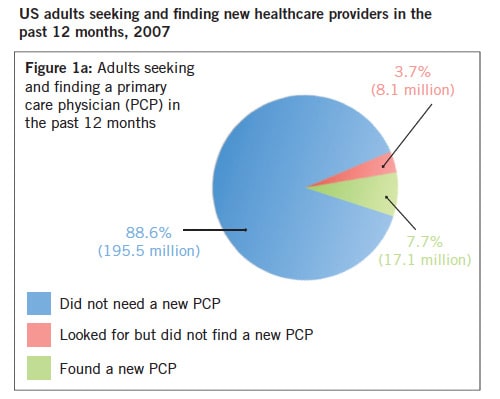

And here’s why we’ve gone too far and why this is important: because tons of people are reading these reviews for more than just a good laugh. I know, you’re thinking exactly what I’m thinking: ‘Do people really scour these review sites looking for a doctor? Do people really make decisions on provider care based on the random comments (positive of negative) of complete strangers?’ Yes. Yes, they do. Some unpublished estimates suggest that upwards of 25% of health seekers will find their doctor online while other research suggests the number might be ‘only’ 1 in 9. Take a look at both graphics in this article. One shows us that about twenty-five million Americans are looking for a new primary care physician in any given twelve-month period (although they don’t always find one, which is a completely separate issue). The second elucidates exactly which information sources are being used by these health seekers to find their primary care physician. Both graphics are ten years old and surely underestimate the actual percentage of people using the internet and the absolute number of people who are looking for a doctor in today’s day and age.

And here’s what else we know: if health seekers are looking for ‘quality’ signals in their choice of a provider, it is conceivable that a set of unfavourable reviews may act as that quality signal. Statistical gurus will tell you that a few bad apples in a barrel of good apples are nothing to worry about and that clinicians ought to encourage all their patients to rate them online so that there are more good reviews (ie apples) in the barrel to drown out the bad ones. The behavioural economists will tell you not to be that sure. They will tell you that as we continue to shift more costs (deductibles, co-pays, etc) to health seekers, their demands about making the right choices about their care are going to be greatly influenced by perceived value. The rallying cry for this group is going to be ‘bang for my buck.’ It is likely that the factors that have a greater perceived impact on quality will be equated with value. And that’s where a couple of (hundred) reviews become important.

We’ve just come out of a brutal American election in which the very real prospect of fake news may have played a role in shaping the opinions of millions and millions of voters. Why is that important? Because there’s a corollary to healthcare. Because fake news is simply a euphemism for ‘user-generated content’. Here’s the entire upshot of this month’s column: how do we validate, authenticate and allow the posting of user generated content in a manner that still allows freedom of expression and thought but doesn’t drive the under-informed to make decisions that are bad for their welfare? (I think I’m still talking about healthcare and not the election of an American President.)

It’s not that I’m against Yelp collecting reviews. It’s not that rating your doctor is necessarily a bad thing. It’s not that I want to stop freedom of speech. It’s not any of those things. As the seventeenth year of this new century has arrived, we need to ask ourselves whether having all this technology means that we have to use it?