Nobel-prize-winning Colombian novelist Gabriel García Márquez once wrote of a mythical town in the middle of the jungle whose residents suffer from a mysterious affliction that erases their memories. Today, in a region of Colombia called Antioquia, reality appears to be imitating fiction – in a way that may answer one of the world’s greatest healthcare challenges.

Antioquia is home to the world’s largest concentration of people who carry a rare genetic mutation that makes them 100% certain to develop Alzheimer’s disease. In most of the world’s population, Alzheimer’s develops because of a mix of genetic and environmental factors and can be nearly impossible to predict. As devastating as Alzheimer’s is anywhere, the Antioquia version is particularly cruel – it strikes people in their mid-40s, progresses rapidly and leads to death about a decade later.

As tragic as this is, it is also a perfect scientific laboratory for finding a cure because, elsewhere in the world, it’s been impossible to predict who will develop Alzheimer’s and who will not, making it hard to study the disease, which typically progresses for decades before being diagnosed.

Antioquia is now the centre of a multimillion dollar, US National Institutes of Health-backed study, which aims to find out for the first time whether Alzheimer’s disease may be preventable. The first data for the landmark Alzheimer’s Prevention Initiative (API) trial of crenezumab is expected early in 2022.

Because of the unique characteristics of the patient population, early therapeutic intervention – before symptoms develop – is being tested, allowing patients to benefit from treatment during the earliest (undetectable) pre- symptomatic stage for the first time.

Some might argue that 2022 is cutting it close when national leaders have set a goal to prevent or effectively treat Alzheimer’s disease by 2025. The API study is different from several high-profile, late-stage pipeline drug failures in recent months – including crenezumab itself – in patients with symptoms of ‘early’ Alzheimer’s disease within the general population. It’s easy to see why hopes of a cure have been dented.

These recent disappointments are painful – none more so, than for all the patients, families and doctors who participated in the clinical trials – but this is not a reason to abandon our efforts. In fact, as in other areas of life, these failures are learning opportunities and we are learning more about the disease and how to treat it.

The reality is we have good reason for optimism – and we have developed a five-point plan, a roadmap to the successful treatment of Alzheimer’s and other neurodegenerative diseases.

One hundred years of solitude

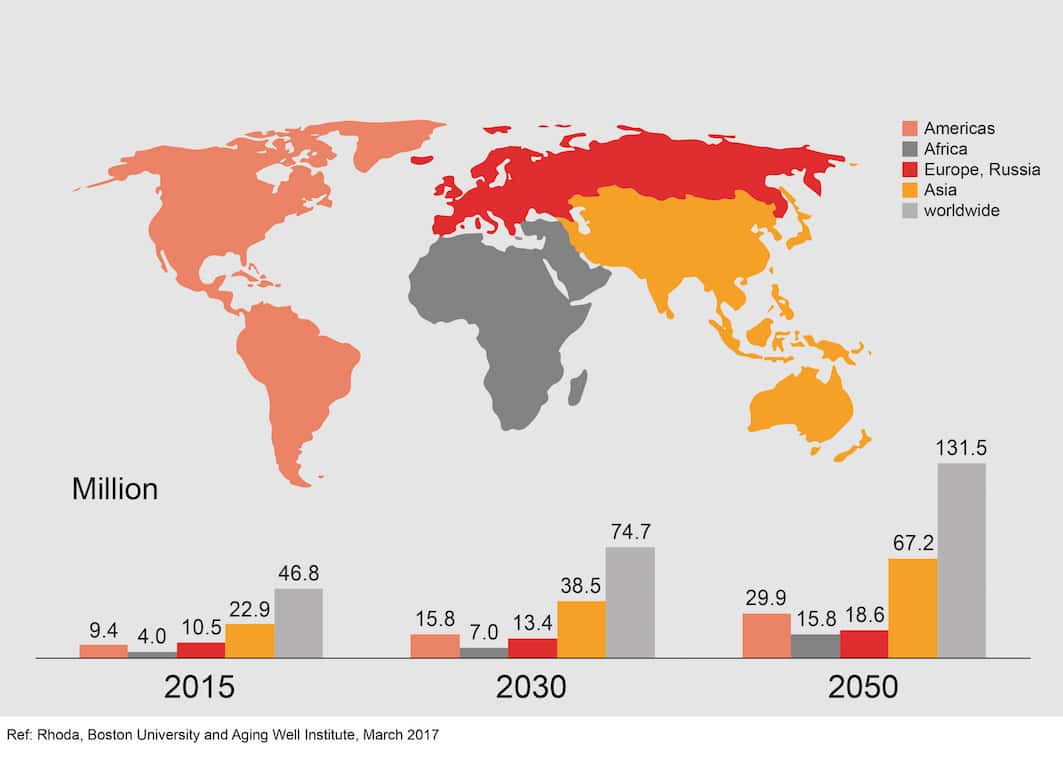

There can be no doubt that dementia is one of the world’s greatest healthcare challenges. Globally, there is a new case of dementia every three seconds. That adds up to around 50 million people worldwide.

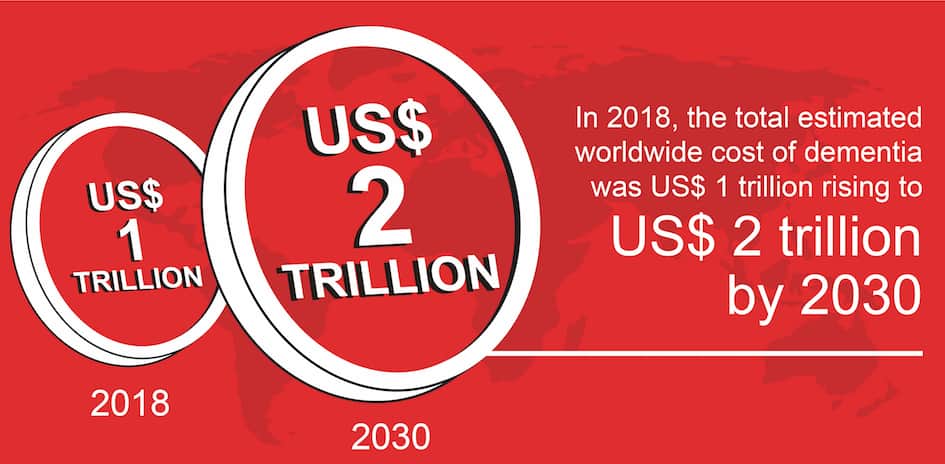

And while it is good news that we are all living longer, healthier lives, it means by 2050, the number of people with dementia is predicted to more than triple to 152 million. Last year, it was estimated that the worldwide cost of dementia stood at US$1 trillion and this stands to increase to US$ 2 trillion by 2030. Yet more than 100 years after the discovery of Alzheimer’s disease, we still do not have a cure.

Success has been limited, with current drugs intended to treat the disease symptomatically. At the same time, a lot of clinical trials are being conducted to combat the disease at its root – the so-called disease-modifying treatments. Until today most of these trials have fallen short of their promises. The question remains why?

Our roadmap to success

Alzheimer’s disease develops because of a complex series of events that take place in the brain over a long period of time. Two proteins – Tau and beta-amyloid – are recognised as major hallmarks of neurodegeneration: tangles and other abnormal forms of Tau protein accumulate inside the brain cells and spread between cells, while plaques and oligomers formed by beta-amyloid occur outside the brain cells of people with Alzheimer’s.

Today, Alzheimer’s disease is typically diagnosed once symptoms are already clinically present. This results in a diagnosis at later stages of the disease where irreversible loss of neurons has already occurred and may go some way to explaining recent research challenges.

Alongside leading voices from academia and industry, we remain in good company in our belief that amyloid plays a role in Alzheimer’s disease. Nevertheless, strategies for developing successful therapeutic interventions are shifting. We have developed a five-point roadmap to successful treatments for Alzheimer’s disease and neurodegenerative diseases.

Firstly, it is now believed that treatments targeting beta-amyloid may only be effective before symptoms become apparent. The challenge is how to identify such individuals within the population, hence the importance of trials like the one in Colombia. Worldwide this is being seen as one of the most important studies in Alzheimer’s disease – to answer the fundamental question of whether beta-amyloid monotherapy will work and if Alzheimer’s disease can be prevented.

Through this work, it may be possible to identify biomarkers that could lead to the development of preventive medicine for use in the wider Alzheimer’s population. This would create a similar situation to cardiovascular disease where we use cholesterol as a biomarker and give statins in a preventative mode.

Secondly, it is well understood that Tau plays a very important role in neurodegeneration and the question we are asking is whether the Tau cellular machinery in early or mild Alzheimer’s disease is already so advanced it can’t be stopped by monotherapy. This is being addressed through multiple Tau research programmes in early and late stage disease, including small molecules intervening at the first step of Tau pathology inside the cell.

Thirdly, while, historically, the role of beta- amyloid has been a significant focus of research, one of the challenges is that multiple pathologies may be contributing to the disease. In other words, there are genetic, lifestyle and environmental factors – to name a few of the most obvious – that may create the conditions leading to Alzheimer’s disease.

The exact aetiologies for different patients may be quite diverse, therefore to understand if a candidate drug has therapeutic potential it is important to identify more homogeneous genetic patient populations. In particular, there are two populations of interest: the Colombian API trial, as already mentioned, and individuals with Down syndrome.

Alzheimer’s disease has been reported in 80% of people with Down syndrome over the age of 40 and 100% over the age of 60. Here, the additional copy of chromosome 21 seems to be the culprit, leading to overproduction of beta-amyloid.

Fourthly, building on the understanding that multiple pathologies contribute to the clinical presentation of Alzheimer’s disease, there is a need to accurately diagnose the underlying pathology and, as such, therapeutic strategies may need to be adapted using precision medicine. In some way it is similar to what we have seen in cancer.

There is no silver bullet but in some cancers there are combinations of drugs that can cure or produce long-term remissions.

Finally, one of the emerging hot topics is the role of neuroinflammation. It has long been known that brain immune cells called microglia maintain a healthy brain environment by clearing debris, including misfolded beta-amyloid, Tau and a-synuclein. Hyper-stimulation of microglial cells is now emerging as a hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease – and could prove a common pathology underpinning all neurodegenerative diseases.

Living to tell the tale

Having worked in cancer research 20 years ago, I recall there was often a feeling across the field that we had hit a brick wall and were not making progress. It was only when we stopped looking at cancer as one disease and started taking a mutation-specific approach that we witnessed recent breakthroughs.

To advance Alzheimer’s research, I believe that there are similar lessons to learn from the advances in cancer, HIV and cardiovascular disease research. For all of us working in the field, we remain in no doubt that this will be not be easy. But in the time it has taken to read this article, around 200 people have been struck with Alzheimer’s disease. We cannot – and should not – look away.