Over the past 15 years, the best-resourced drug development teams on earth have spent billions on Alzheimer’s disease. Yet none of these programmes has yielded a drug approval, making Alzheimer’s R&D perhaps the least effective use of money in pharma or any other industry. Faced with that litany of failures, researchers are branching out beyond old approaches to amyloid- beta (Abeta) in search of effective therapeutics.

Alzheimer’s R&D is defined by huge numbers on both sides of the ledger. While the 99%-plus failure rate is a big deterrent, projections that one in every 85 people alive in 2050 will have Alzheimer’s are a huge incentive. If a drug that delays the onset of Alzheimer’s by one year comes to market by 2020, 9.2 million fewer people would have the disease by 2050. Such a drug would make blockbuster sales.

Many efforts to seize that opportunity have centred on Abeta, peptides that are found in plaques in Alzheimer’s patients. Alzheimer’s hits early in genetic subpopulations with high levels of Abeta but, despite these apparent links between the peptides and disease, clinical programmes targeting plaques have failed.

Each failure provided a clue about how to do better in the future, however, from the importance of targeting Abeta oligomers to the need to avoid dose-limiting toxicities. AC Immune and Roche factored these lessons into the development of crenezumab. In January, that drug was added to the long list of Abeta candidates to fail in phase 3.

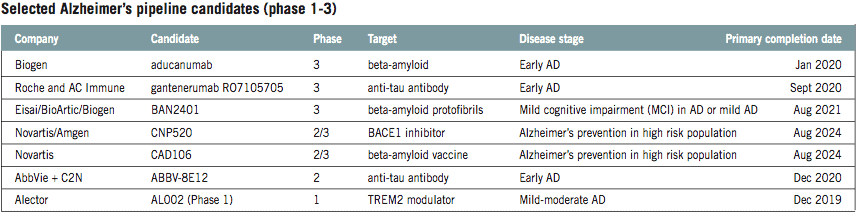

Another crushing blow to hopes came on 21 March, when Biogen and Eisai pulled the plug on their phase 3 Abeta-targeting aducanumab. It remains possible that some of the failed candidates were good therapies tested on the wrong patients, even so, it now looks unlikely that any Abeta drug will be a silver bullet.

That is reflected in the diversification of the pipeline. As of January 2018, more than half of phase 3 Alzheimer’s assets were anti-amyloid therapies. In phase 2, the figure fell to less than one-third. Data on the early-stage pipeline is lacking but anecdotal evidence suggests it is more diverse still. Whereas in the past the sector had “a very singular focus on amyloid”, Sosei Heptares’ chief R&D officer Malcolm Weir said he now thinks it is looking at targets “in a slightly more sophisticated way”.

“I’m not saying that amyloid is not involved, but I think people are looking more broadly at targets that may be involved in the pathogenesis and the pathophysiology of Alzheimer’s disease,” Weir said.

The expansion of Alzheimer’s R&D is underpinned by evidence that the disease has a range of drivers, including Abeta, inflammation and epigenetics, that evolve as it progresses. This evidence has spurred research and led

organisations including the Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation and AC Immune to conclude that combination therapies may be needed to tackle such a complex disease.

Targeting tau

Tau is among the beneficiaries of the broader focus and emerging interest in combination therapies. Abeta plaques and neurofibrillary tangles of tau proteins are the two main pathological features

of Alzheimer’s. Research suggests the burden of tau tangles correlates more closely with cognitive decline than the load of amyloid plaques, but the target remains relatively untested.

That is starting to change. While anti-tau drugs make up 4% of the phase 3 pipeline, the number rises to 14% in phase 2 and still more assets are in research and early-phase development. Rising interest in tau is reflected in a series of deals involving AC Immune.

Since 2012, AC Immune has partnered tau assets with Roche’s Genentech, Johnson & Johnson and Eli Lilly. The drugs include antibodies that capture tau as it spreads between cells and small molecules designed to enter cells and inhibit tau aggregation. These mechanisms may be complementary.

“We think combination therapies between … antibodies and small molecules make a lot of sense,” AC Immune CEO Andrea Pfeifer said.

AC Immune and its partners are far from the only drug developers to target tau. AbbVie is testing its anti-tau antibody ABBV-8E12 in a phase 2 trial, while Biogen has links to two midphase tau programmes. The big biotech is testing its own BIIB092 in early Alzheimer’s patients and has an option to develop an Ionis Pharmaceuticals’ antisense drug designed to reduce production of tau in the brain.

Expanding frontiers

While Abeta and tau are the defining features of Alzheimer’s, there is evidence that other proteins such as alpha-synuclein and TBT-43, plus inflammation, oxidative stress and other factors, may act on disease progression or influence responses to drugs. Equally, researchers are still coming up with novel ways to target Abeta and tau. And there is scope to improve the lives of Alzheimer’s patients without slowing the progression of the disease, for example by hitting targets that improve cognition.

In pursuit of these opportunities, R&D groups are searching for new targets and re-evaluating ones discarded in the past. Sosei Heptares’ work on M1 falls into the latter category. Eli Lilly took an M1 agonist, xanomeline, into phase 3 in the 1990s and emerged with evidence that the drug improves cognition. However, xanomeline didn’t make it to market as the side effects were so severe that more than half of the patients who received the high dose in one trial dropped out.

While M1 agonists only treat the symptoms of Alzheimer’s, rather than slow or stop the progression of the disease, the efficacy seen in the 1990s was tantalising enough to spur years of research. Much of this research centred on improving the selectivity of compounds so that they hit the target, M1, without also interacting with similar receptors linked to the intolerable side effects.

Those efforts foundered but in recent years interest in M1 has increased. Sosei Heptares landed a $125m upfront payment from Allergan on the strength of its work to create more selective M1 agonists, although parts of its clinical programmes are on hold pending an investigation into preclinical toxicology data. Meanwhile, Karuna Pharmaceuticals has raised $42m to resurrect Lilly’s xanomeline by using a second drug to prevent side effects.

Other groups, including Sosei Heptares, are working on novel ways to modify the disease itself. In the UK, Wren Therapeutics is analysing the chemical kinetics of protein misfolding to find novel ways to treat diseases including Alzheimer’s. The work builds on research at the University of Cambridge that discovered a molecule that reduced the production of Abeta in early-stage tests.

Elsewhere, J&J is working with the University of Pennsylvania on gene therapies capable of triggering the production of antibodies in the brain. Denali Therapeutics is collaborating with Sanofi on a drug designed to alleviate inflammatory responses and reduce plaque by inhibiting RIPK1. And a host of other academic and industry teams are looking at epigenetics, oxidative stress and much more.

In parallel, diagnostic groups are working to improve the detection and stratification of Alzheimer’s patients. These lower-profile efforts could yield huge gains by enabling companies to identify patients with the mix of Abeta, tau and other factors that render them susceptible to particular therapeutics.

“I’m actually convinced if we have very precise diagnostics the field will all change,” Pfeifer said.

Cautious optimism

The more nuanced understanding of the biology of Alzheimer’s and advances in diagnostics that are now emerging provide cause for cautious optimism. If the multifactorial image of Alzheimer’s that researchers are sketching proves to be accurate and continues to improve, future R&D programmes will at least try to act on some or all of the key pathways. When coupled to improved patient selection, that advance could be significant enough to finally yield a breakthrough.

Similar statements have been made before, however. In the early 2000s, emerging knowledge of tau tangles and Abeta plaques, plus imaging advances, fuelled R&D and offered encouragement that the pathology of the disease was starting to come into focus. Fifteen years, billions of dollars and tens of failed clinical programmes later, it is clear the then-emerging knowledge painted an incomplete picture.

The situation today has enough parallels to the historical precedent to temper optimism that major near-term improvements in the treatment of Alzheimer’s are likely. Yet, as the rapid pace of progress in cancer shows, decades of unsung research into disease biology can rapidly turn into a torrent of innovation once a tipping point is reached.

N.B. This article was updated on 21 March 2019 following news of Biogen and Eisai’s termination of the aducanumab trials.

Read more: Brain power: fresh approaches to Alzheimer’s drug discovery