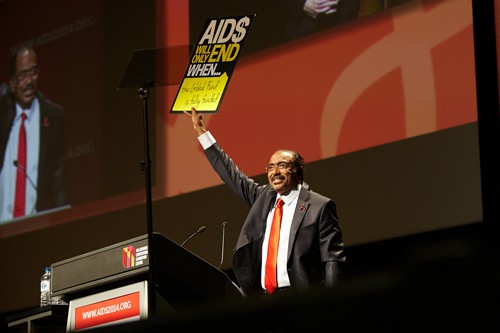

Michel Sidibé, executive director of UNAIDS

News of the re-emergence of HIV in a girl thought to have been cured of the infection through early treatment is already a major talking point as Aids 2014 gets underway in Melbourne.

While the finding was a major blow to hopes of a therapeutic cure for people exposed to the virus, the opening plenary session at the conference sounded a positive note, with Michel Sidibé, executive director of UNAIDS, suggesting it was feasible to end the Aids epidemic by 2030.

Sidibé’s vision for tackling the disease does not rely on finding a cure, rather expansion of existing responses such as widespread testing and access to treatment, with each person living with HIV achieving viral suppression, and robust preventive measures so no-one is born with the virus.

Clearly, there are massive obstacles in the way of that objective, not least the crisis in paediatric Aids, epidemic of tuberculosis in infected people and the high price of newer drugs and diagnostics, he said, singling out the cost of drugs for hepatitis C, a relatively common co-infection with HIV. Meanwhile, discrimination remains a major barrier to treatment in many parts of the world.

By 2020, the objective should be for 90 per cent testing coverage, 90 per cent of people living with HIV on treatment and 90 per cent virally suppressed, he said, adding: “If we are smart and scale up fast by 2020, we will be on track to end the epidemic by 2030.”

With delegates at the conference still reeling from the news of their lost colleagues on Flight MH17, Sidibé said that the 2030 challenge was shared by “my friend and mentor Joep Lange. His vision will stay with me until it becomes a reality”.

The focus on making the best use of established control measures chimes with new animal research – just published in Nature – which suggests HIV can form reservoirs in the body that are protected from antiviral drugs even before the virus is detected in the blood.

Monkeys exposed to the HIV-like simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) were treated with antiretroviral therapy as early as three days after infection but even this timely intervention failed to stop the virus re-emerging once dosing stopped.

Despite this sobering finding, conference c-chair Prof. Sharon Lewin of Monash University in Australia pointed to other research suggesting “we can wake up the virus reservoir and make enough of the virus to leave the cell, making it visible to an immune response,” even though the focus of efforts for an HIV cure was currently on developing treatments leading to remission.

“As a scientist, I remain passionate that the search for a vaccine and cure must continue,” she said, pointing out that the re-emergence of HIV in the four-year-old US girl was an opportunity for new lines of research.

“There is much to learn from this extraordinary case. It is our job now, as scientists, to understand why such prolonged remission was achieved and more importantly how to make that durable,” she said.

Sounding a similarly positive note, Prof. Françoise Barré-Sinoussi, International Conference Chair of Aids 2014 and president of the International AIDS Society told the conference that the scale up of HIV programmes has “begun to reverse the spread of HIV,” with 14m people in low- and middle-income countries now on treatment.

“But we need to step up the pace,” she added. “Many countries are still struggling to address their HIV epidemic and … key affected populations are consistently being left behind.”